Authors:

Quantinuum (alphabetical order): Eric Brunner, Steve Clark, Fabian Finger, Gabriel Greene-Diniz, Pranav Kalidindi, Alexander Koziell-Pipe, David Zsolt Manrique, Konstantinos Meichanetzidis, Frederic Rapp

Hiverge (alphabetical order): Alhussein Fawzi, Hamza Fawzi, Kerry He, Bernardino Romera Paredes, Kante Yin

What if every quantum computing researcher had an army of students to help them write efficient quantum algorithms? Large Language Models are starting to serve as such a resource.

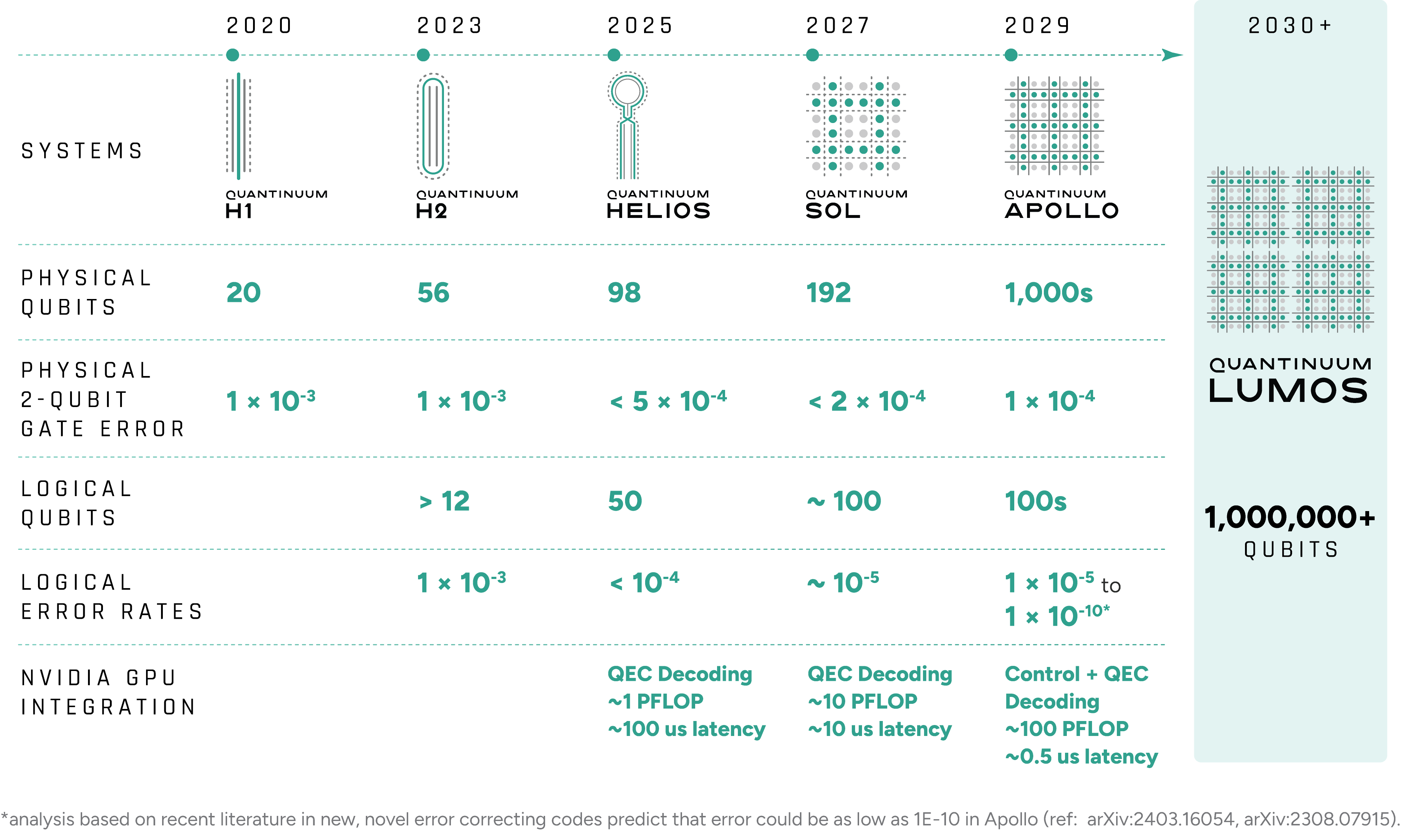

Quantinuum’s processors offer world-leading fidelity, and recent experiments show that they have surpassed the limits of classical simulation for certain computational tasks, such as simulating materials. However, access to quantum processors is limited and can be costly. It is therefore of paramount importance to optimise quantum resources and write efficient quantum software. Designing efficient algorithms is a challenging task, especially for quantum algorithms: dealing with superpositions, entanglement, and interference can be counterintuitive.

To this end, our joint team used Hiverge’s AI platform for automated algorithm discovery, the Hive, to probe the limits of what can be done in quantum chemistry. The Hive generates optimised algorithms tailored to a given problem, expressed in a familiar programming language, like Python. Thus, the Hive’s outputs allow for increased interpretability, enabling domain experts to potentially learn novel techniques from the AI-discovered solutions. Such AI-assisted workflows lower the barrier of entry for non-domain experts, as an initial sketch of an algorithmic idea suffices to achieve state-of-the-art solutions.

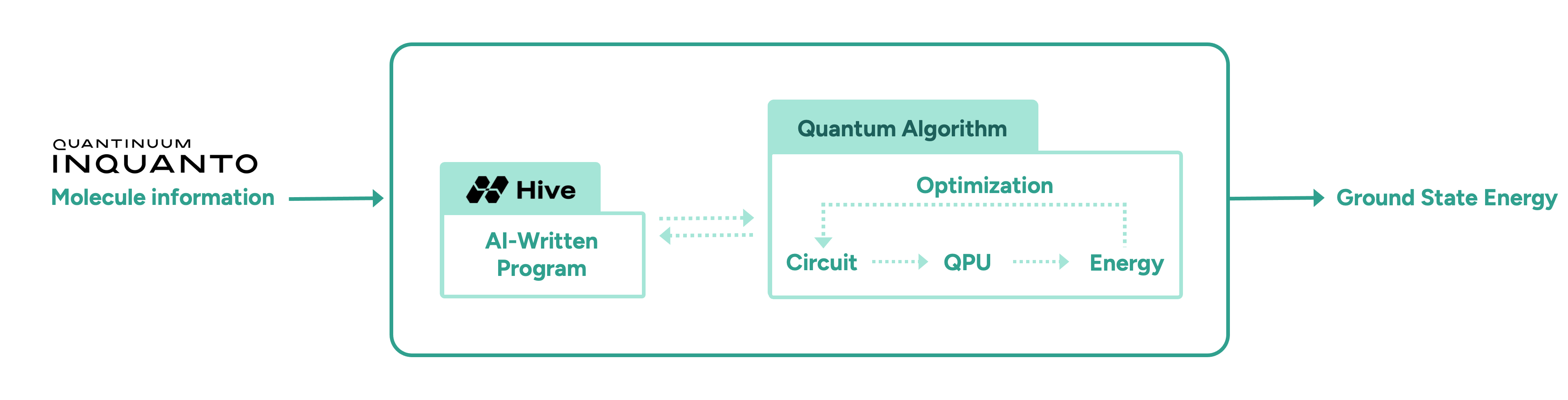

In this initial proof-of-concept study, we demonstrate the advantage of AI-driven algorithmic discovery of efficient quantum heuristics in the context of quantum chemistry, in particular the electronic structure problem. Our early explorations show that the Hive can start from a naïve and simple problem statement and evolve a highly optimised quantum algorithm that solves the problem, reaching chemical precision for a collection of molecules. Our high-level workflow is shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the quantum algorithm generated by the Hive achieves a reduction in the quantum resources required by orders of magnitude compared to current state-of-the-art quantum algorithms. This promising result may enable the implementation of quantum algorithms on near-term hardware that was previously thought impossible due to current resource constraints.

The Electronic Structure Problem in Quantum Chemistry

The electronic structure problem is central to quantum chemistry. The goal is to prepare the ground state (the lowest energy state) of a molecule and compute the corresponding energy of that state to chemical precision or beyond. Classically, this is an exponentially hard problem. In particular, classical treatments tend to fall short when there are strong quantum effects in the molecule, and this is where quantum computers may be advantageous.

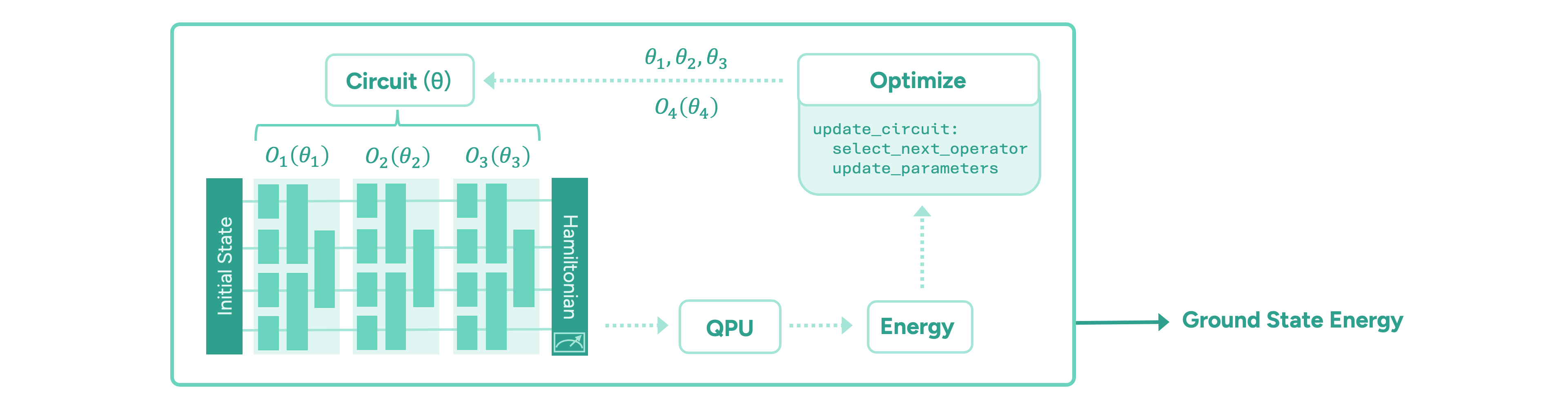

The paradigm of variational quantum algorithms is motivated by near-term quantum hardware. One starts with a relatively easy-to-prepare initial state. Then, the main part of the algorithm consists of a sequence of parameterised operators representing chemically meaningful actions, such as manipulating electron occupations in the molecular orbitals. These are implemented in terms of parameterised quantum gates. Finally, the energy of the state is measured via the molecule’s energy operator, the “Hamiltonian”, by executing the circuit on a quantum computer and measuring all the qubits on which the circuit is implemented. Taking many measurements, or “shots”, the energy is estimated to the desired precision. The ground state energy is found by iteratively optimising the parameters of the quantum circuit until the energy converges to a minimum value. The general form of such a variational quantum algorithm is illustrated in Figure 2.

The main challenge in these frameworks is to design an appropriate quantum circuit architecture, i.e. find an efficient sequence of operators, and an efficient optimisation strategy for its parameters. It is important to minimise the number of quantum operations in any given circuit, as each operation is inherently noisy and the algorithm’s output degrades exponentially. Another important quantum resource to be minimised is the total number of circuits that need to be evaluated to compute the energy values during the optimisation of the circuit parameters, which is time-consuming.

To meet these challenges, we task the Hive with designing a variational quantum algorithm to solve the ground state problem, following the workflow shown in Figure 1. The Hive is a distributed evolutionary process that evolves programs. It uses Large Language Models to generate mutations in the form of edits to an entire codebase. This genetic process selects the fittest programs according to how well they solve a given problem. In our case, the role of the quantum computer is to compute the fitness, i.e., the ground state energy. Importantly, the Hive operates at the level of a programming language; it readily imports and uses all known libraries that a human researcher would use, including Quantinuum’s quantum chemistry platform, InQuanto. In addition, the Hive can accept instructions and requests in natural language, increasing its flexibility. For example, we encouraged it to seek parameter optimisation strategies that avoid estimating gradients, as this incurs significant overhead in terms of circuit evaluations. Intuitively, the interaction between a human scientist and the Hive is analogous to a supervisor and a group of eager and capable students: the supervisor provides guidance at a high level, and the students collaborate and flesh out the general idea to produce a working solution that the supervisor can then inspect.

We find that from an extremely basic starting point, consisting of a skeleton for a variational quantum algorithm, the Hive can autonomously assemble a bespoke variational quantum algorithm, which we call Hive-ADAPT. Specifically, the Hive evolves heuristic functions that construct a circuit as a sequence of quantum operators and optimise its parameters. Remarkably, the Hive converged on a structure resembling the current state-of-the-art, ADAPT-VQE. Crucially, however, Hive-ADAPT substantially outperforms this baseline, delivering significant improvements in chemical precision while reducing quantum resource requirements.

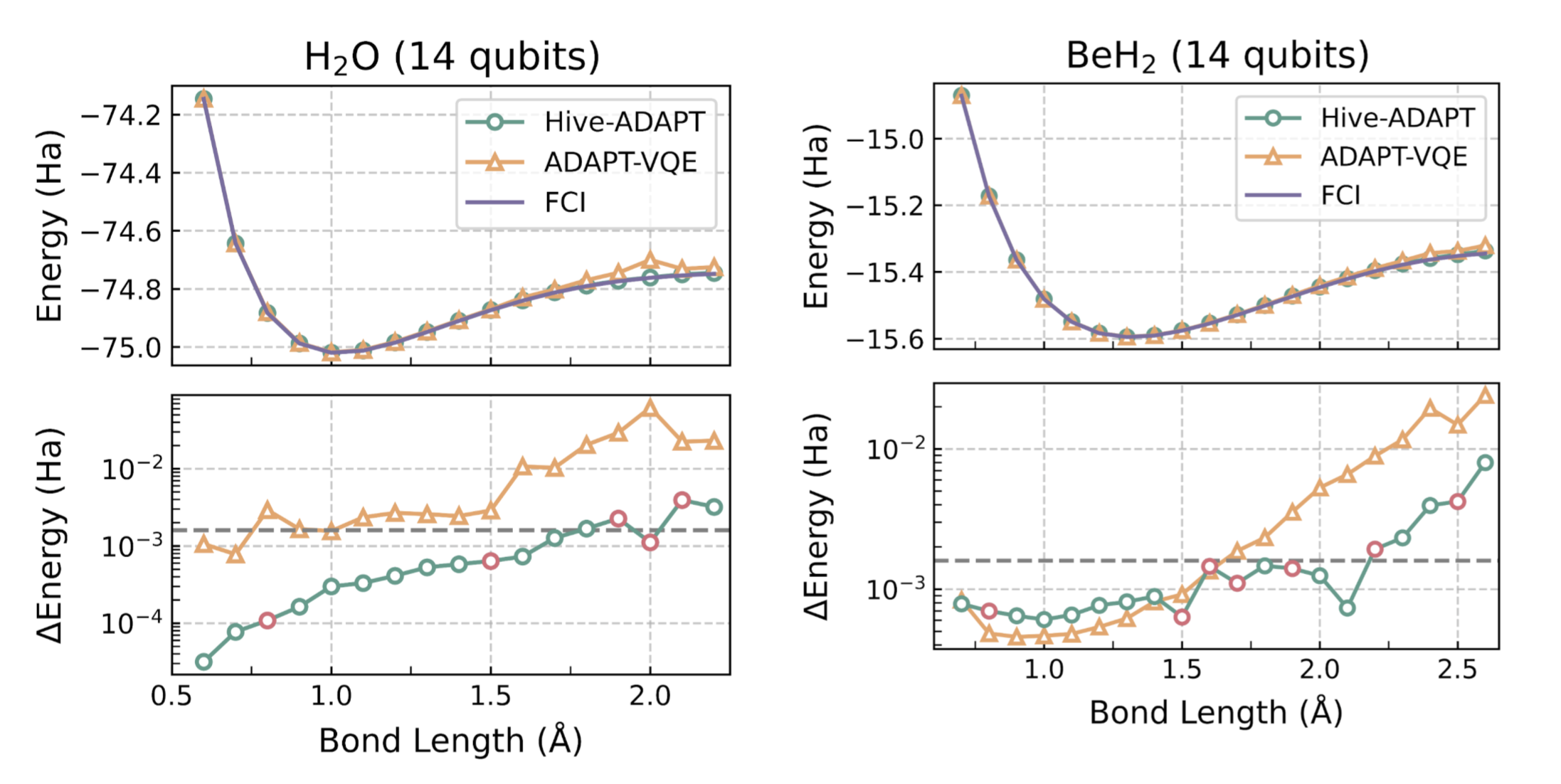

A molecule’s ground state energy varies with the distances between its atoms, called the “bond length”. For example, for the molecule H2O, the bond length refers to the length of the O-H bond. The Hive was tasked with developing an algorithm for a small set of bond lengths and reaching chemical precision, defined as within 1.6e-3 Hartree (Ha) of the ground state energy computed with the exact Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) algorithm. As we show in Figure 3, remarkably, Hive-ADAPT achieves chemical precision for more bond lengths than ADAPT-VQE. Furthermore, Hive-ADAPT also reaches chemical precision for other “unseen” bond lengths, showcasing the generalisation ability of the evolved quantum algorithm. Our results were obtained from classical simulations of the quantum algorithms, where we used NVIDIA CUDA-Q to leverage the parallelism enabled by GPUs. Further, relative to ADAPT-VQE, Hive-ADAPT exhibits one to two orders of magnitude reduction in quantum resources, such as the number of circuit evaluations and the number of operators used to construct circuits, which is crucial for practical implementations on actual near-term processors.

For molecules such as BeH2 at large Be-H bond lengths, a complex initial state is required for the algorithm to be able to reach the ground state using the available operators. Even in these cases, by leveraging an efficient state preparation scheme implemented in InQuanto, the Hive evolved a dedicated strategy for the preparation of such a complex initial state, given a set of basic operators to achieve the desired chemical precision.

To validate Hive-ADAPT under realistic conditions, we employed Quantinuum’s H2 Emulator, which provides a faithful classical simulator of the H2 quantum computer, characterised by a 1.05e-3 two-qubit gate error rate. Leveraging the Hive's inherent flexibility, we adapted the optimisation strategy to explicitly penalise the number of two-qubit gates—the dominant noise source on near-term hardware—by redefining the fitness function. This constraint guided the Hive to discover a noise-aware algorithm capable of constructing hardware-efficient circuits. We subsequently executed the specific circuit generated by this algorithm for the LiH molecule at a bond length of 1.5 Å with the Partition Measurement Symmetry Verification (PMSV) error mitigation procedure. The resulting energy of -7.8767 ± 0.0031 Ha, obtained using 10,000 shots per circuit with a discard rate below 10% in the PMSV error mitigation procedure, is close to the target FCI energy of -7.8824 Ha and demonstrates the Hive's ability to successfully tailor algorithms that balance theoretical accuracy with the rigorous constraints of hardware noise and approach chemical precision as much as possible with current quantum technology.

For illustration purposes, we show an example of an elaborate code snippet evolved by the Hive starting from a trivial version:

Quantinuum’s in-house quantum chemistry expert, Dr. David Zsolt Manrique, commented,

“I found it amazing that the Hive converged to a domain-expert level idea. By inspecting the code, we see it has identified the well-known perturbative method, ‘MP2’, as a useful guide; not only for setting the initial circuit parameters, but also for ordering excitations efficiently. Further, it systematically and laboriously fine-tuned those MP2-inspired heuristics over many iterations in a way that would be difficult for a human expert to do by hand. It demonstrated an impressive combination of domain expertise and automated machinery that would be useful in exploring novel quantum chemistry methods.”

Looking to the Future

In this initial proof-of-concept collaborative study between Quantinuum and Hiverge, we demonstrate that AI-driven algorithm discovery can generate efficient quantum heuristics. Specifically, we found a great reduction in quantum resources, which is impactful for quantum algorithmic primitives that are frequently reused. Importantly, this approach is highly flexible; it can accommodate the optimisation of any desired quantum resource, from circuit evaluations to the number of operations in a given circuit. This work opens a path toward fully automated pipelines capable of developing problem-specific quantum algorithms optimised for NISQ as well as future hardware.

An important question for further investigation regards transferability and generalisation of a discovered quantum solution to other molecules, going beyond the generalisation over bond lengths of the same molecule that we have already observed. Evidently, this approach can be applied to improving any other near-term quantum algorithm for a range of applications from optimisation to quantum simulation.

We have already demonstrated an error-corrected implementation of quantum phase estimation on quantum hardware, and an AI-driven approach promises further hardware-tailored improvements and optimal use of quantum resources. Beyond NISQ, we envision that AI-assisted algorithm discovery will be a fruitful endeavour in the fault-tolerant regime, as well, where high-level quantum algorithmic primitives (quantum fourier transform, amplitude amplification, quantum signal processing, etc.) are to be combined optimally to achieve computational advantage for certain problems.

Notably, we’ve entered an era where quantum algorithms can be written in high-level programming languages, like Quantinuum’s Guppy, and approaches that integrate Large Language Models directly benefit. Automated algorithm discovery is promising for improving routines relevant to the full quantum stack, for example, in low-level quantum control or in quantum error correction.